It has been 25 years since Indira Gandhi was assassinated by two of her Sikh bodyguards.

Tussling over Teresa

One of the quietest, most peaceful places in the heart of Kolkata is Mother House.

85,000

That’s how many Iraqis died in the war between 2004 and 2008. Iraq’s human rights ministry released that grim number a week ago.

We keep an exact count of the number of Americans who were killed in Iraq and Afghanistan. Or the number of British troops and other coalition members. But no one really counts the civilians. The children. The mothers. The grandmothers. They remain nameless, numbing numbers in headlines. “42 died in suicide bombing.”

“Outlawed groups through terrorist attacks like explosions, assassinations, kidnappings or forced displacements created these terrible figures, which represent a huge challenge for the rule of law and for the Iraqi people,” the ministry said.

“These figures draw a picture about the impact of terrorism and the violation of natural life in Iraq,” the ministry said in a draft report on deaths in Iraq.

But no one really knows how many Iraqis died.

The Iraqi government report was compiled with death certificates issued by the health ministry. What about all those people who never saw home again. Or whose families never reported a death out of sheer fear.

I know people who have lost loved ones and kept silent. One death in the family was enough.

Some Iraqis were killed by AK-47 fire, rockets, mortars, and bombs, otherwise known as improvised explosive devices. Some were abducted, stabbed or beheaded. In places like Ramadi, such gruesome acts were carried out in public places and in broad daylight.

The capital of al-Anbar province was once al-Qaida’s haven and an Iraqi citizen’s hell on Earth — the neighborhood of Melaab was known as “the heart of darkness.”

But one bullet, one bomb — is all it takes.

C’est la vie

A few years ago, my cousin’s young wife told me that she looked forward to turning 50.

When the earth shook and a girl smiled

The earthquake in Sumatra took me back to Gujarat. 2001.

Will you remember me?” 14-year-old Bhavika Vegad asked peering straight into my camera, the smile disappearing from her face.

How could I not? Bhavika’s world was turned upside down when a Jan. 26 earthquake leveled her city. And I was there to bear witness.

All around her, relatives, friends, classmates and teachers perished under the concrete and bricks that tumbled to the ground the day the earth roared in Anjar.

Six days later, a sprightly Bhavika roamed the rubble-filled streets, shielding her nose from the dust and dodging the debris in her path. She followed me from a temporary clinic and shelter halfway to the devastated Mistry Failyu neighborhood.

“I miss going to school, ” she said in almost perfect English. “I miss my friends and teachers.”

No one knew when Bhavika would be able to return to school. Anjar, with 65,000 residents, is a bit bigger than Roswell. And the only thing left here is misery.

Now the journalists have started to leave Gujarat state. The relief agencies are also temporary. But Bhavika’s life has changed forever.

And, yet, in the midst of Gujarat’s tragedy, her face was a ray of hope — an inspiration to begin healing.

When I first arrived in Ahmedabad, the former state capital that has roughly the same population as the Atlanta metro area, the scale of the devastation eluded me. The airport in this industrial center is located in an area that was largely spared.

It was two days after the massive temblor. It was midnight. I had been traveling for almost 24 hours.

I felt lucky that I had been able to reserve a hotel room in a city suddenly bursting at the seams with media, dignitaries and relief workers. All I wanted was the comfort of a clean bed.

The first sign that something was terribly wrong struck me as the auto-rickshaw made its way deeper into the heart of Ahmedabad. So many people were out in the streets — some of them sleeping under the stars, others too scared to close their eyes.

When I arrived at the hotel, the deep fissures in the wall made me wonder whether I, too, might not be better off sleeping in the street.

“This hotel is not safe, ” the auto-rickshaw driver said.

That was all it took. That first night I slept in a dump across from the railway station. But it was a dump without cracks in the walls.

I found a better room on my second day in Ahmedabad, in the Best Western Moti Manor. But I didn’t realize that the rail tracks ran past the back of the building. Every time a train went by, my heart raced at the thought that another aftershock might be rattling the city.

The seismology experts said Gujarat was experiencing aftershocks at the rate of one every hour. It was hard to sleep at night, knowing that the walls could crumble around me at any moment.

It was then that I understood the fear and panic that had gripped this part of the world.

Usually, we find solace in our homes. But here, a two-minute temblor had robbed Gujaratis of that fundamental comfort in life. People regarded their homes not as a place of sanctuary but as a menace, an enemy.

As I visited town after town in Gujarat’s Kutch region, I realized the enormity of what had happened. Entire towns and villages lay flattened. Thousands of people were left out on the fields and streets with nothing left to their names. Out of every pile of rubble wafted the acrid smell of rotting corpses. Men and women wailed openly. Others, shellshocked, grieved in silence. Or didn’t feel at all.

In Anjar, I walked from block to block surrounded by desperate rescue workers. Four hundred dead here. Thirty-two still trapped there. Renu Suri of the Atlanta-based relief and development agency CARE had warned me the death toll is certain to be much higher than reported. She said as many as 100,000 people could have died, but that we may never know with certainty.

I thought of a conversation I’d had a week before the quake with a friend in Calcutta. We agreed that India, the world’s second-most populous country, would go nowhere without family planning. India’s best method of population control, he added, came in the form of natural calamities. We need more cyclones and floods, he said.

I thought his statement gross then. In Anjar, the words became unbearable.

Back in Calcutta, I showed my family a video of Gujarat recorded on my camcorder. As Bhavika Vegad’s face lit up the TV screen, I wondered what she was doing at that moment, 12 days after the quake.

Was she still sleeping in the cold? Was she afraid of entering a cracked building? Had her school reopened? How many of her friends died in the quake?

Bhavika told me her parents had survived. So I knew she was one of the lucky ones.

Yes, Bhavika, I will always remember you. I’ll remember your long black braid bouncing down your back as you ran.

Your smile was the only one I saw in Anjar.

Gandhi Jayanti

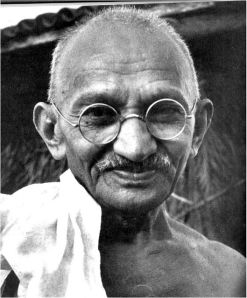

I know several folks who were born today. They share their birthday with one of history’s greatest men: Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. Otherwise known as Mahatma, the great soul.

Goddess of strength

Thousands of deities are on their way to the banks of the Ganges in West Bengal today. The immersions have to be finished by Wednesday in the capital, Kolkata.

Ma Durga, the goddess of strength, returns to Ma Ganga, the holiest of rivers.

In the next few hours, murtis or images made from clay, wood, paper mache, bamboo, straw, shell and sand will begin dissolving in murky river waters.

Durga Puja, the biggest Hindu festival in my home state, is culminating this week.

When I was young, Durga Puja was the highlight of my year. Like an American kid looking forward to Christmas.

The five-day festival usually falls in September or October, depending on the position of the stars. We were off from school for several weeks. The streets were filled with fun and food. We wore new outfits for each day of the puja and went from pandal to pandal (temporary structures that housed the images) to see which one was the biggest, the baddest.

Hindu mythology tells the tale of Durga this way: Only a woman could kill the demon named Mahishasur. So the gods got together and each gave a virtue and skill to create the ultimate warrior, the goddess of strength. They gave Durga 10 arms so she could carry weapons in each to slay the Earth’s evil.

And so she did.

As I grew older and Kolkata became more congested, Durga Puja became somewhat of an inconvenience. The crowds, the road closings, the heat, the rain, the mud and muck of the dwindling monsoons. Last year, I almost missed my flight back to Atlanta because it took so long to weave through city streets to get to the airport.

The 15 million people of Kolkata all seem to be out together during Durga Puja. The constant banging of the dhol (drums) and blaring Bollywood music deafens my ears. At the end of every street, on every corner and in the neighborhood parks and schools, clubs fight for best in show. Who will win the prize for the most attractive Durga display? Some images are realistic. Others abstract. Some simple, others so ornate they would make Marie Antoinette gasp.

And when the five days of worship are over, throngs of people parade down the streets behind a lorry carrying their neighborhood Durga to the Ganges, so she can return to the heavens.

Whether you get into the Hindu puja spirit or not, there is something awesome about seeing millions of people fall at the feet of a woman to worship her strength, especially in a country like India, where women still have a long way to go to gain equal standing with men.

Last year, I was walking home from the bank and I stood and watched workers put the finishing touches on their Durga display. The beautiful and mighty woman, steely in body and soul (and loaded with weapons to boot!).

I stared into the eyes of the image. And felt her strength recharge me.

Check out this Web site for more information on the ceremony, rituals and story behind Durga:

Betrayal

In the summer of 2004, when word came that John Kerry had tapped former presidential rival John Edwards as his running mate, I climbed into my Honda CRV and drove fast and furious up Interstate 85 from Atlanta to Edwards’ hometown of Robbins, North Carolina.

In the summer of 2004, when word came that John Kerry had tapped former presidential rival John Edwards as his running mate, I climbed into my Honda CRV and drove fast and furious up Interstate 85 from Atlanta to Edwards’ hometown of Robbins, North Carolina.

In the Jungle

Late one night, I was flipping channels and came across a 2002 docudrama made by Michael Winterbottom called “In This World.”

The camera followed two Afghan brothers, Jamal and Enayatullah, on a harrowing journey from a Peshawar refugee camp through the Middle East and Europe. Because they were crossing borders illegally, the risks were enormous. They climbed snowy mountains without warm boots, were smuggled out in crowded trucks and shipped in stifling hot containers.

I won’t tell you how that particular journey ends – you will have to watch the movie.

But this morning, the French government dismantled “the Jungle,” a makeshift camp that housed men who had fled their homelands in search of prosperity in Europe. They were all illegal; most had been motivated to flee because of persecution. I would think that they ought to qualify for refugee status.

They go to Calais with hopes in their heart of one day crossing the English Channel into Britain, which for some reason has developed a reputation as a haven for illegal migrants.

On a clear day you can see the white cliffs of Dover from the French coast. The men from Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Somalia and other troubled lands, cast their eyes across the 20-mile stretch of water, wondering if there is a future for them across the waves.

Just like the brothers in Winterbottom’s movie, they hope to be smuggled into England, perhaps hidden underneath a lorry crossing the water by ferry.

Illegal immigration has, of course, become a big problem in Europe. Hence, the crackdown. The French government has not yet said what will become of the migrants who were detained Tuesday. Humanitarian workers are pressing both Britain and France to take in those who are at great risk.

One Afghan man told CNN reporter Phil Black that the Taliban had accused him of being a spy. He feared for his life in Afghanistan and left his family behind to seek a safer prospect. Tuesday, the uncertainty in his life became greater. He only knew one thing for sure. He could not turn around and go back home.

A different sort of revolutionary

Norman Borlaug died over the weekend.

Who?

OK. Borlaug’s name isn’t familiar to most, though he was one of only five people to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal. The other four recipients are Martin Luther King Jr., Nelson Mandela, Elie Wiesel, and Mother Teresa.

So why was Borlaug in such esteemed company?

He is credited with saving millions from starvation. Not through philanthropy but with science.

He collaborated first with Mexican scientists and then with Indians and Pakistanis on efforts to improve wheat production. High-yield, disease-resistant wheat varieties pioneered by Borlaug in the 1960s led to successful increases in food production and earned him the title of father of the agricultural “Green Revolution.”

In my native India, Borlaug’s plant science was considered a godsend at a time when the nation could not match food production rates to a burgeoning population. Green Revolution technology enabled India to go from famine to agricultural self-sufficiency.

For helping alleviate human misery in developing nations, Borlaug won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970. The Statesman newspaper in India hailed him this week as the greatest hunger fighter of all time.

“It is true that the tide of the battle against hunger has changed for the better during the past three years,” he said in his Nobel acceptance speech in Oslo, Norway. “But tides have a way of flowing and then ebbing again. We may be at high tide now, but ebb tide could soon set in if we become complacent and relax our efforts. For we are dealing with two opposing forces, the scientific power of food production and the biologic power of human reproduction.”

Some people say the ebb tide has set in. That Borlaug’s science didn’t really work. Millions of people suffer from food shortages.

Borlaug blamed high rates of population growth in defending himself against critics who argued that Borlaug’s science had created more problems than it had solved. Environmentalists said Green Revolution technology relied too much on chemicals and toxic pesticides. Social critics said it hurt small farmers.

But some humanitarian workers still hail him as a saviour.

“No single person has contributed more to relieving world hunger than our friend, the late Norman Borlaug,” said Rev. David Beckmann, president of Bread for the World. “Normanwas truly the man who fed the world, saving up to a billion people from hunger and starvation.”

Josette Sheeran, the executive director of the United Nations World Food Programme said this: “His total devotion to ending famine and hunger revolutionized food security for millions of people and for many nations.”

Last month, Iowa Sens. Chuck Grassley, a Republican, and Democrat Tom Harkin introduced legislation to designate Borlaug’s birthplace and childhood home near Cresco, Iowa, as a National Historic Site. He was born on a farm there on March 25, 1914.

“Dr. Borlaug and his work to save the lives of hundreds of millions people are historically significant for Iowa,” Grassley said in a press release. “By designating his birthplace and boyhood home a National Historic Site, we’ll be preserving his legacy for years to come and continuing to inspire future generations of scientists and farmers to innovate and lift those mired in poverty.”

Maybe now, more people will know Norman Borluag’s name.