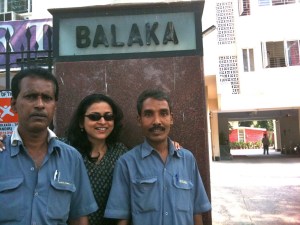

The flat in the building called Balaka (which means swan in Bengali) at 68 B Ballygunj Circular Road is no longer my home. After nine-and-a half years of caring for it from across the globe, I completed the final act of an arduous sales process in Kolkata.

I’ve posted a photo taken out front this week. With me are Kalu and Bimal, two men who have done menial jobs at the building for most of the years my parents lived there.

In that flat, simple and not so large by American standards, I laughed, loved and lost. It was home for so many years.

It was there that my mother regained her verve for life after a massive stroke nearly took her life in 1982. She gained freedom in her small way, learning to wheel herself around the rooms and hallways with ease, poking her head into the kitchen and instructing the housekeeper how to make perfect Bengali fish curry.

Some evenings, she arranged for musicians to come to the flat. We’d sit on rugs on the floor and sing the songs of Tagore. My mother’s voice was gone when she was left half paralyzed, but she belted it out anyway. I sometimes caught her eyes watering. She lamented little after the stroke but I knew she yearned to play again the harmonium and sing the songs she loved most.

In the morning, after she had her third round of Darjeeling tea, she picked up the phone and called our relatives and friends to learn news of their lives. My mother was the glue that held our family together. When she died, I stopped knowing details about my aunts and uncles, cousins and friends.

It was there in that flat that my father sat at the dining room table for hours pruning his bansai plants. He filled the verandahs with greenery. The dahlias bloomed with fierce, spreading hues of reds, pinks and oranges across the view.

Or he sat with his magnifying glass struggling to read newspapers when the macular degeneration in his eyes began to blur his world. He often worked out his mathematical and statistical theories in his head, his hands moving in the air as though there was a chalkboard before him. He had made a name for himself in probability theory. Later in life, when Alzheimer’s began winning the battle, my father could not add two plus two.

Everything changed today when I signed over the final documents to the man who purchased our flat earlier this year. I waited in the West Bengal registration office for a long time, sandwiched between a zillion people in a British-era building now filled with cobwebs and dust.

My friend Vijay (on the right in the registration office photo) made it all happen for us. Without him, my brother and I might have still be mired in West Bengal bureaucracy. I really don’t know how to ever thank him.

But for a moment, after I signed the final document, I felt as though I had wronged my parents somehow. As though I had given away the place where they had found solace. I asked the new owner if I could take the brass nameplate on the door that carried my father’s name. (photo)

Then I descended down the long British Raj era staircase, its terrazo warped by footsteps from many decades. I turned back only once. And left with my memories, brilliant like diamonds.