<img style="float:left; margin:0 10px 10px 0;cursor:pointer; cursor:hand;width: 20

0px; height: 150px;” src=”https://evilreporterchick.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/deirdre32.jpg?w=300″ border=”0″ alt=””id=”BLOGGER_PHOTO_ID_5616037014890889698″ />

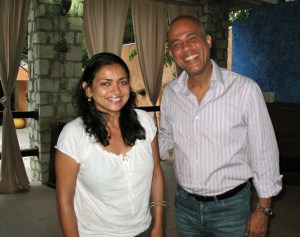

We meet Deirdre Stoelze Graves in Casper on a day when the clouds have given way to sun for a few moments and the wind is blowing like it always does in Wyoming. Deirdre came out here many years ago to get away from it all on the East coast. She got a job as a cop reporter for the Casper paper — even gave us the crime tour of the city — and ended up staying two decades.

Along the way she married a cowboy. I have only spoken to Dale twice — on the phone, when I called Deirdre to talk Dart Society business. That’s how I first met her, in 2008, when I won a Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma fellowship and spent a week in Chicago. I liked her instantly. She is such a free spirit. Crazy. Fun. Generous. Kind. And the heartbeat of the Dart Society.

Still, I am a bit unsure about staying with her. I have heard so much about her husband and the ranch but it all feels so alien to me, the city girl who revels in the bleakest urban jungle. Deirdre navigates us up Interstate 25 to Kaycee. A town had once thrived here but flooding destroyed much of it a few years back. Now, mostly, it is a collection of trailers and a few downtown buildings that survived, two bars and a general store that sells spaghetti for almost $3 a box.

From Kaycee, we drive anther 20 lonely miles inward. Rolling hills and fields of cattle and sheep give way to the sight of the Big Horn Mountains. This is Broke Back Mountain territory, where Jack Twist couldn’t quit Ennis del Mar in, perhaps, an exaggerated story of love between ranch hands. It snowed in the morning, Dierdre tells me. The mountains are white. We drive further in, past red sandstone cliffs that remind me of Arizona, before we arrive at the doublewide trailer that Deirdre and Dale and their little boy Elliot call home. It’s expensive to build a house out here, Dale says. It’s much easier to plop down a trailer.

It has rained and snowed and is now raining again and the fields, normally dry at this time of year, are like vats of peanut butter mud. My boots sink in and my mind in taken back instantly to Iraq, where trekking through mud on U.S. military bases had become a daily thing.

We get inside Deirdre’s cozy abode and fill our bellies with salami sandwiches and homemade pumpkin pie. It is so quiet here. No distractions, save nature’s fury and the barking of Clyde, the family dog who is ordered to chase the neighbor’s beef cows away from Deirdre and Dale’s property. They’ll eat every last blade of grass, Dale says.

Dale is tall, lanky. He’s not wearing cowboy boots or a cowboy hat. He’s gentle and tolerant of Deirdre’s friends who have interrupted the solace of his Sunday. But he’s unmistakably a cowboy. The sun has deepened the lines of his face. They run like the rivers that cut the canyons out here.

Dale drives us to one of those canyons. We stand on the very edge — no tourist barriers here — and I strain to see the water many feet below. Deirdre and Dale were married here, they tell me. Suddenly, heaven seems closer and it doesn’t matter that the rain has started up again. I am well covered in Dale’s oil skin ranch coat and Deirdre’s cowboy boots.

I’d seen all this only in movies before.

Deirdre says she feels too isolated out here these days. She craves interaction with people who can relate to her. Most folks around here see her as a hippie chick, the only Obama supporter around for many miles. But Dale grew up here and besides a vacation to Italy, he’s hardly left Wyoming. And never will. Ranching is in his blood. He wouldn’t know how to make a living any other way.

My dear friend has to reconcile her love with her lifestyle. She talks about it as we cram into the back of Dale’s pickup and slush back to the house. Inside, Elliot prances about the counters and furniture. If he could, he’s climb the walls. He has Deirdre’s energy.

She breaks out the white linens for dinner. We sip tempranillo and watch the sun go down. We watch The Red Wall, as the sandstone is known, glow in the light. And listen to the silence outside. It is a life I could not have imagined before.