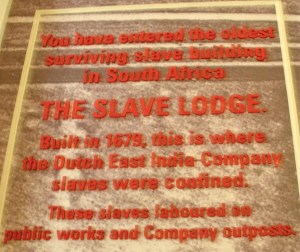

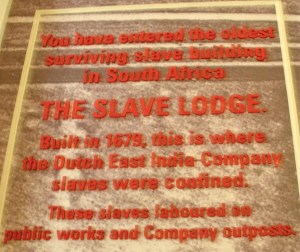

I will start my southern Africa journey here, at the Slave Lodge in Cape Town.

It is not where I physically began my 10-day trip to this part of the world. But it is where I choose to begin — in a place of beginnings and endings, of hate and love, of breathtaking natural landscapes and ugly scars of human cruelty.

For all the magnificence I have seen on this incredible trip — lions in the wild, one of the seven natural wonders of the world and the collision of two great oceans at the Cape of Good Hope — nowhere did I shed more tears than in this stark rectangular building that once housed thousands of human beings who were not recognized as such.

Today, the oldest slave lodge in South Africa looks beautiful in structure. (See picture.) But go back in time.

There were no windows then, just slits in the wall. People manacled and tied together in a manner worse than animals. They spent hot, suffocating nights here. During the day, they were marched out to toil.

The tourist guide books don’t tell you much about the wretched history of South Africa. My book dedicated most of its Slave Lodge blurb to the architectural splendor of the building, not to the unimaginable pain that was borne here.

It is now a museum dedicated to those whose names will be forgotten by history. They are no Vasco de Gamas or Simon Van der Stels (for whom the now famous Stellenbosch winelands are named). Just ordinary people plucked from their homes and taken to suffer and die.

I stood before a map that showed all the places from where the Dutch brought in their human captives. My eyes went straight to India. Malabar. Cochin. And yes, Kolkata. I stared at the Bengal dot on the map of South Asia. I felt a hot drop land on my clenched fists.

I thought of my mother telling me stories about British colonial rule in India and the picture at my grandfather’s house of a water fountain in Maniktola: “Europeans,” it said on one side. “Indians and dogs,” on the other.

I sat in the dark museum, staring at images of mothers torn from sons and daughters, separated forever. I heard the clack of wooden clogs slaves were forced to wear here so that their Dutch masters could hear them if they tried to move at night.

I imagined.

And for all the death and war I have seen, I could not ever feel the sorrow of this non-life that thousands of people, including my ancestors, lived through.

Or didn’t.

I have many friends in the United States who tell me personal stories of racism. Their ancestors were slaves. Their parents lived through segregation. I recalled my conversations with the poet Natasha Tretheway. Of racism, hate, ignorance.

I grew up with stories about Bapuji, father of the nation. That’s how Indians revere Mahatma Gandhi. I read about how Gandhi, as a young lawyer, fought for rights in South Africa. We all know what he did when he returned to India.

School was filled with history lessons on the East India Company, the Dutch, the Portuguese and the British. I grew to womanhood familiar with colonialism’s fury.

Yet, I had never felt its sting in India — I was fortunate to have been born 15 years after independence. I felt it more in the Deep South but never in ways that were physically or psychologically damaging to me.

So here I stood, in lovely Cape Town, surrounded by majestic landscape, and all I saw was heartbreak and blood. It was mapped out before me, on a museum wall.

It was the first thing I saw in Cape Town. And for the next few days, I would think of nothing else.

Next: A guide with a view.