Can A White Guy Lead An Organization Founded For Journalists of Color?.

via Can A White Guy Lead An Organization Founded For Journalists of Color?.

Random thoughts in war and peace

I just returned from a short trip to a part of central India that was previously unfamiliar — Gadchiroli District in the state of Maharashtra. I was there to report a rape story for CNN and traveled with CNN cameraman Sanjiv Talreja and producer Harmeet Shah Singh.

Photojournalist Vivek Singh also accompanied us. He’s a freelancer based in Delhi and we’ve used his work on CNN’s photo blog. I edited the text that ran with an amazing gallery about rising tensions between Bodo tribespeople and Bengali Muslims in northeastern India. It was refreshing to see journalism from India that goes far beyond the breathless and sensational stuff that is common in the media here.

Vivek’s work is hauntingly beautiful. Powerful. Sometimes stark in black and white. It’s difficult to take your eyes off his images. I was lucky he was able to make it to Gadchiroli with us.

Check out Vivek’s work here:

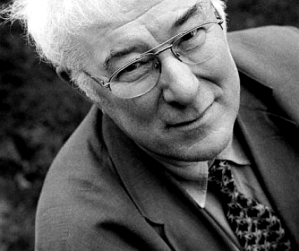

Seamus Heaney died today. The New York Times headline described him as “Irish poet of soil and strife.”

Seamus Heaney died today. The New York Times headline described him as “Irish poet of soil and strife.”

I don’t pretend to always understand poetry though I savor it. I am always awed by how poets use language in such an artful way. My favorite poet of all time remains Pablo Neruda, who is simply magical to me. Seamus Heaney was another writer I have admired for a long time.

The world has lost another terrific writer today.

Here is my favorite verse by Heaney from his poem, “Casualty.”

My mother would have turned 82 today. I would have picked up the phone and called her. 011-91-33-2247-6600.

I would have said: Ma! Happy Birthday. I would have asked her what she was doing to celebrate.

She would have said that my pishi (aunt) was coming over for lunch. Nothing special was planned.

I wold have asked about what else was going on. She would have given me family updates — she kept in touch with everyone. She was the glue. She would have caught me up with gossip about the neighbors in our flat building.

She would have hurried through the conversation to get to the most important part. When will you come to Kolkata?

I would have said: In mid-September, Ma. I will be there soon.

I would have imagined her smile. She would have told me how she couldn’t wait to see me.

I will get on a plane to go home next week but she won’t be there waiting for me.

Happy Birthday, beautiful Ma. I miss you every waking moment.

Thursday evening, I drove out to Loganville, Georgia. I suppose it’s not a tremendous distance from downtown Atlanta but during rush hour, it took me more than an hour before I turned right onto Georgia Highway 81, named the Michael Stokely Memorial Highway.

It was the eighth anniversary of Mike’s death.

He went to Iraq with the 48th Infantry Brigade and was killed by a bomb in the Iraqi town of Yusufiya. I covered his memorial service in Iraq and later, when I returned home, I wrote about his father, Robert Stokely, and how he coped with his son’s death. I visited Mike’s grave with Robert one year after Mike died. Friends and family gathered to remember the fallen soldier at the exact time of his death. 2:20 a.m. in Iraq.

Over the years, I kept in touch with Robert; quoted him in several of my Iraq stories and wrote a longer piece about his own journey to Yusufiya a couple of years ago. He felt he would never have closure until he touched the dirt where his son fell. That journey did not turn out as Robert had planned it but it was healing nevertheless. You can read the story on CNN.com.

I’ve always felt grateful to Robert for sharing the details of his punctured life. It’s important, I believe, for America to know it has helped others cope with their grief.

Not too many people showed up this year for the annual gathering at Mike’s grave. As Robert said, people move on with their lives. We said our hellos and made conversation. It had already rained Thursday and the clouds looked down at us with a threat of more to come. We talked about how it was unusually cool for August, almost chilly, how it has rained so much this summer that Robert didn’t have to buy gallon jugs of water to keep the grass green over Mike’s grave.

There was nothing formal about the gathering. Just family and friends remembering Mike and reflecting on the path our lives have taken.

Before I began covering the Iraq War at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, I never called anyone in uniform a friend. But now I know many people in the military. Before, I was like many Americans who are oblivious to the toll of war. Not any more.

On the way home on 1-20, I thought about Robert standing on the ground above his son’s coffin. He asked everyone to remember the men and women who gave their lives fighting for their country. To many, he said, they are just soldiers. To us, they are sons, daughters, fathers, mothers, brothers and sisters.

Today is not Veteran’s Day or Memorial Day but for families like the Stokelys, every day is one of remembrance.

It’s too bad “Midnight’s Children” was a bust at the box office. I’m thinking that Deepa Mehta was perhaps the wrong director to give us the celluloid depiction of Salman Rushdie’s terrific book, which won the Booker Prize in 1981.

The protagonist and narrator of Rushdie’s story, Saleem Sinai, is born at the exact moment when India gained independence from Britain. The film, had it been a success, might have broadened knowledge of the painful history of my homeland, just like “Gandhi” had done years before. “Gandhi” won various Oscars in 1983, including best picture.

At 11:57 p.m. on August 14, 1947, the nation of Pakistan was born, carved out of land that was a part of British India. Five minutes later, at 12:02 a.m. on August 15, India was declared a free nation. To all my Pakistani and Indian friends: Happy Independence Day.

That independence came with a steep price. British India was partitioned along religious and political lines. Pakistan became the Muslim homeland and Muslims living in lndia crossed borders on the west and east. At the same time, Hindus and Sikhs in the new Pakistan made the trek to India. At least 10 million people were uprooted from their homes; some estimates say it was as many as 25 million.

It was far from peaceful, far from what Mahatma Gandhi, the father of non-violence had anticipated.

Hindus and Muslims butchered each other. Sometimes, entire trains from Punjab to Pakistan arrived with seats and bunks awash in red. Or vice versa. Women were raped; children slaughtered. There are no exact counts of the dead; just an estimate of 250,000 to 2 million.

Gandhi’s non-violent revolution turned exceedingly bloody. Brother against brother. Blood spilled in the name of religion.

My father’s generation remembers that ugly time in our history. His family was displaced from their home in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and started over in Calcutta. I heard stories from him and his friends and other Indians I have met from that era.

Atlanta physician Khalid Siddiq was one of those people. He told me he boarded a crowded train in New Delhi with his parents and four siblings to make a terrifying two-day journey through the farmlands of Punjab.

“I was very young but I think I understood what was happening,” he told me. “I could see the fear and anguish on my father’s face. It was a terrifying experience for everybody.”

Sohan Manocha told me he witnessed hundreds of killings as a young Hindu boy in Punjab. “That kind of horror leaves memories that are hard to erase, ” he said.

The stories of the painful birth of India and Pakistan are dying with the people who lived it. I am sorry I never recorded my conversations with people I knew.

Luckily, an oral history project, 1947 Partition Archive, is doing just that.

“The 1947 Partition Archive is a people-powered non-profit organization dedicated to documenting, preserving and sharing eye-witness accounts from all ethnic, religious and economic communities affected by the Partition of British India in 1947,” the website says. “We provide a platform for anyone anywhere in the world to collect, archive and display oral histories that document not only Partition, but pre-Partition life and culture as well as post-Partition migrations and life changes.”

I’m glad someone took the time to preserve history.

It’s especially important since tensions between India and Pakistan have never settled.

Just last week, five Indian soldiers were killed last week along the heavily militarized Line of Control, the de facto border in the disputed region of Kashmir. Since then skirmishes have flared tension between the two rival nations. Again. (India and Pakistan have already fought two full-scale wars over Kashmir, which Pakistan argues should have been a part of the newly formed Muslim nation in 1947.)

So on this Independence Day, I remember all those lives that were lost in the making of free nations, in the making of our destinies.

Last weekend, I went to a trunk show of jewelry crafted by my friend Anubha Jayaswal. She’s a friend from my hometown, Kolkata; her husband Vishal loves Bengali food more than I do. That’s true homage to the cuisine of my culture.

Anubha works in the frenzied world of finance but when she has spare time, she makes jewelry. Check out her stuff on her Sky Jewelry page on Facebook.

I bought a couple of pieces and enjoyed the afternoon talking with desi girls who, like me, are not big fans of the ornate gold stuff you see in Indian wedding photos.

Many years ago, I walked through the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto, mesmerized that the history of mankind could be told through footwear — from caveman to Christian Laboutin. I was fascinated, given my penchant for shoes. (Yes, I have way too many.)

So when I stumbled upon the Tassen Museum Hendrikje in Amsterdam recently, I had to go in. Housed in a beautiful old building on Herengracht, the museum pays homage to, what else, handbags. It’s not as extensive as the shoe museum but tells a 500-year-history of handbags and purses in the Western world. Through bags, you get a good idea of how social norms changed for women.

And the museum shop is terrific if you are in the market for a good bag.

On the Fourth of July, I ask you:

Should African-Americans celebrate this day? They were slaves when the Declaration of Independence was crafted. Should Native Americans celebrate this day? The white man obliterated them from their lands.

Or perhaps the right question to ask is: How should people of color celebrate American independence? The answer is varied and often, personal.

I am proud to have become an American citizen. I love this country.

But I also understand its brutal history of racism. I know that this day means many things to many people.

Here is Frederick Douglass on the “Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro:” http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/douglassjuly4.html

As a reporter, I have numerous conversations every day with people I don’t know that well or at all. Once in a while, those conversations strike a chord. That’s what happened a few days ago in my 30-minute discussion with Col. Kevin Brown.

I’d met Brown in Baghdad in 2005; he was commander of a 10th Mountain Division battalion (Triple Deuce), to which a Georgia guard company I was embedded with was attached. I saw him now and then when he interacted with the soldiers I was writing about and then in the context of “Baby Noor,” an Iraqi girl with spina bifida who the soldiers flew to America for life-saving treatment.

You can read my stories about Noor on CNN.com: “Iraq’s Baby Noor: An Unfinished Miracle” and the followup story for which I called Brown recently.

I knew Brown was a smart man. He was now a retired Army colonel pursuing a PhD in security studies. He was a high-ranking officer who was well-liked by his soldiers — I didn’t hear that often about battalion commanders.

But our phone conversation struck me. Brown was forthcoming and deeply philosophical about his years at war and how Iraq had affected him and others. Though he is largely unfamiliar to me, at times in the conversation, I felt I was talking to my best friend. I knew exactly how he felt. I felt comforted by the words on the other end of the phone.

“Perhaps the Noor story shines that light on a time when we were good men and earned our nation’s respect whether they were looking or not … whether they knew it or not, and it gives us some comfort amongst the shades of gray we experienced there,” he said.

At that moment, I knew that my follow-up story on Noor had to center on Brown. He had captured the essence of the story with his words. I hope you will read it on CNN.com.

It’s not a big, bad, breaking news story. And in the grand scheme of things, Noor’s story, as I say in my piece, is a blip in the overall chaos and sorrow of the Iraq War.

But it’s stories like these that keep me going as a journalist. Because in the most basic way, they confirm our humanity and keep me believing there is good in people. Without that, after all, there is little meaning in our lives.