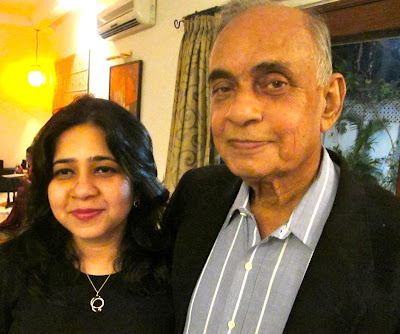

Hasan Zeya used to boast about how he was still practicing medicine into his early 80s. But at 84, he no longer is happy about his age. His daughter, Rena, passed away last week, days shy of her 52nd birthday.

“She did a bad thing. She cut ahead of me in the queue,” he tells me at her funeral Sunday.

Tears well in his eyes, though he keeps a brave front among the hundreds of people who have come to pay tribute to Rena. The weather, dreary and wet, matches the mood inside the inside Temple Kol Emeth.

Rena’s memorial was exactly how it should have been. A rabbi and grieving husband spoke of her incredible talent, compassion and ability to inspire. They spoke of a daughter, a wife, a mother, who gave her all to her family.

Rena worked for many years at CNN, a majority of her time spent as a leader at CNN International. The temple was filled with journalists who stood in awe of her.

Watch a birthday message from Dr. Zeya to Rena on her birthday last year:

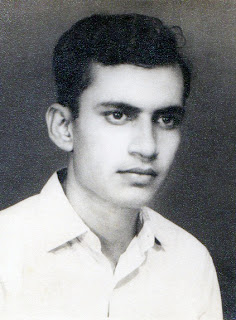

Dr. Zeya tells me how his own father had been a journalist in India but discouraged his son from ever becoming one. It was hard work and no money. But maybe that’s where Rena got her passion.

As a little girl, Rena would make her parents watch as she pretended to be a news anchor. She would hide under the table and appear from behind the tablecloth to the deliver the news.

Rena came to America on her sixth birthday. Dr. Zeya had wanted a better life for his family and moved to North Carolina from a remote part of the Indian state of Bihar. His family hailed from the place where Mahatma Gandhi launched his civil disobedience campaign in India — there’s a scene in the Oscar winning film that shows Gandhi arriving at that train station.

Dr. Zeya tells me he was happy to leave what he called the “most backward place in India.” For a variety of reasons.

He tells me he loved that in Chapel Hill, he could shower with hot water spewing from the faucets. And that he did not have to sweat through the entire summer like we did in India when the electricity went out and the fans stopped for hours. I felt connected with him — and to Rena — in a whole different way.

I never really spoke with Rena much about her early childhood in India. My connections to our homeland, of course, were much stronger since my parents chose to return there many years ago. But in a strange sort of way, it was comforting to know now that Rena had experienced life as I had there. She was only a year and half older than me.

My deepest connection to Rena was that when I first met her more than 20 years ago, she was the only other Indian woman I knew in mainstream journalism in the United States. Now, of course, there are many successful South Asian women practicing great journalism. But back then, there were few. Rena knew that and encouraged women like me to keep pushing forward.

As I speak with her father, I realize where she got a lot of her spunk, though he insists that it was she who inspired him.

Dr. Zeya tells me he never wanted to color his children’s thoughts about big things in life. Like religion. He wanted Rena to make up her own mind. It was exactly how my father had raised my brother and me. He never allowed organized religion to infiltrate our home. He wanted us to figure it out for ourselves.

Sunday afternoon, Dr. Zeya sat in the temple to hear Rabbi Steven Lebow tell the audience what Rena had said to him when it became apparent she was going to die.

She told him she didn’t fear death — she never had in her painful two-year battle against lymphoma. She worried only about what would happen to her children, Sabrina and Adam, and to the love of her life, her husband, Rob Golden.

She also told Rabbi Lebow that she wasn’t religious, though she considered herself deeply spiritual. It was a statement that made her father proud.

We spoke of religious tensions in India. Dr. Zeya sipped Sprite and launched a conversation on Islam. He believes followers of that faith must rethink their path to the future. It was not a discussion I’d expected to have at Rena’s funeral and at first, I was caught by surprise.

But on the long drive back home on 1-75, I decided otherwise. My conversation with Dr. Zeya was exactly what Rena would have wanted. Smart, forward-thinking, outside-the-box, provocative, even, and totally unexpected at a funeral. She would have liked that her father initiated an intelligent conversation with her friends and colleagues.

The rain came down harder. It was as though the entire world was mourning the loss of Rena Shaheen Zeya Golden.