A few years ago, my cousin’s young wife told me that she looked forward to turning 50.

When the earth shook and a girl smiled

The earthquake in Sumatra took me back to Gujarat. 2001.

Will you remember me?” 14-year-old Bhavika Vegad asked peering straight into my camera, the smile disappearing from her face.

How could I not? Bhavika’s world was turned upside down when a Jan. 26 earthquake leveled her city. And I was there to bear witness.

All around her, relatives, friends, classmates and teachers perished under the concrete and bricks that tumbled to the ground the day the earth roared in Anjar.

Six days later, a sprightly Bhavika roamed the rubble-filled streets, shielding her nose from the dust and dodging the debris in her path. She followed me from a temporary clinic and shelter halfway to the devastated Mistry Failyu neighborhood.

“I miss going to school, ” she said in almost perfect English. “I miss my friends and teachers.”

No one knew when Bhavika would be able to return to school. Anjar, with 65,000 residents, is a bit bigger than Roswell. And the only thing left here is misery.

Now the journalists have started to leave Gujarat state. The relief agencies are also temporary. But Bhavika’s life has changed forever.

And, yet, in the midst of Gujarat’s tragedy, her face was a ray of hope — an inspiration to begin healing.

When I first arrived in Ahmedabad, the former state capital that has roughly the same population as the Atlanta metro area, the scale of the devastation eluded me. The airport in this industrial center is located in an area that was largely spared.

It was two days after the massive temblor. It was midnight. I had been traveling for almost 24 hours.

I felt lucky that I had been able to reserve a hotel room in a city suddenly bursting at the seams with media, dignitaries and relief workers. All I wanted was the comfort of a clean bed.

The first sign that something was terribly wrong struck me as the auto-rickshaw made its way deeper into the heart of Ahmedabad. So many people were out in the streets — some of them sleeping under the stars, others too scared to close their eyes.

When I arrived at the hotel, the deep fissures in the wall made me wonder whether I, too, might not be better off sleeping in the street.

“This hotel is not safe, ” the auto-rickshaw driver said.

That was all it took. That first night I slept in a dump across from the railway station. But it was a dump without cracks in the walls.

I found a better room on my second day in Ahmedabad, in the Best Western Moti Manor. But I didn’t realize that the rail tracks ran past the back of the building. Every time a train went by, my heart raced at the thought that another aftershock might be rattling the city.

The seismology experts said Gujarat was experiencing aftershocks at the rate of one every hour. It was hard to sleep at night, knowing that the walls could crumble around me at any moment.

It was then that I understood the fear and panic that had gripped this part of the world.

Usually, we find solace in our homes. But here, a two-minute temblor had robbed Gujaratis of that fundamental comfort in life. People regarded their homes not as a place of sanctuary but as a menace, an enemy.

As I visited town after town in Gujarat’s Kutch region, I realized the enormity of what had happened. Entire towns and villages lay flattened. Thousands of people were left out on the fields and streets with nothing left to their names. Out of every pile of rubble wafted the acrid smell of rotting corpses. Men and women wailed openly. Others, shellshocked, grieved in silence. Or didn’t feel at all.

In Anjar, I walked from block to block surrounded by desperate rescue workers. Four hundred dead here. Thirty-two still trapped there. Renu Suri of the Atlanta-based relief and development agency CARE had warned me the death toll is certain to be much higher than reported. She said as many as 100,000 people could have died, but that we may never know with certainty.

I thought of a conversation I’d had a week before the quake with a friend in Calcutta. We agreed that India, the world’s second-most populous country, would go nowhere without family planning. India’s best method of population control, he added, came in the form of natural calamities. We need more cyclones and floods, he said.

I thought his statement gross then. In Anjar, the words became unbearable.

Back in Calcutta, I showed my family a video of Gujarat recorded on my camcorder. As Bhavika Vegad’s face lit up the TV screen, I wondered what she was doing at that moment, 12 days after the quake.

Was she still sleeping in the cold? Was she afraid of entering a cracked building? Had her school reopened? How many of her friends died in the quake?

Bhavika told me her parents had survived. So I knew she was one of the lucky ones.

Yes, Bhavika, I will always remember you. I’ll remember your long black braid bouncing down your back as you ran.

Your smile was the only one I saw in Anjar.

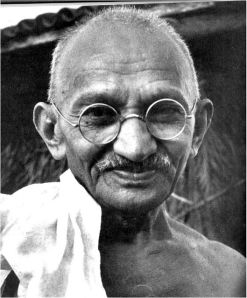

Gandhi Jayanti

I know several folks who were born today. They share their birthday with one of history’s greatest men: Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. Otherwise known as Mahatma, the great soul.

Betrayal

In the summer of 2004, when word came that John Kerry had tapped former presidential rival John Edwards as his running mate, I climbed into my Honda CRV and drove fast and furious up Interstate 85 from Atlanta to Edwards’ hometown of Robbins, North Carolina.

In the summer of 2004, when word came that John Kerry had tapped former presidential rival John Edwards as his running mate, I climbed into my Honda CRV and drove fast and furious up Interstate 85 from Atlanta to Edwards’ hometown of Robbins, North Carolina.

In the Jungle

Late one night, I was flipping channels and came across a 2002 docudrama made by Michael Winterbottom called “In This World.”

The camera followed two Afghan brothers, Jamal and Enayatullah, on a harrowing journey from a Peshawar refugee camp through the Middle East and Europe. Because they were crossing borders illegally, the risks were enormous. They climbed snowy mountains without warm boots, were smuggled out in crowded trucks and shipped in stifling hot containers.

I won’t tell you how that particular journey ends – you will have to watch the movie.

But this morning, the French government dismantled “the Jungle,” a makeshift camp that housed men who had fled their homelands in search of prosperity in Europe. They were all illegal; most had been motivated to flee because of persecution. I would think that they ought to qualify for refugee status.

They go to Calais with hopes in their heart of one day crossing the English Channel into Britain, which for some reason has developed a reputation as a haven for illegal migrants.

On a clear day you can see the white cliffs of Dover from the French coast. The men from Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Somalia and other troubled lands, cast their eyes across the 20-mile stretch of water, wondering if there is a future for them across the waves.

Just like the brothers in Winterbottom’s movie, they hope to be smuggled into England, perhaps hidden underneath a lorry crossing the water by ferry.

Illegal immigration has, of course, become a big problem in Europe. Hence, the crackdown. The French government has not yet said what will become of the migrants who were detained Tuesday. Humanitarian workers are pressing both Britain and France to take in those who are at great risk.

One Afghan man told CNN reporter Phil Black that the Taliban had accused him of being a spy. He feared for his life in Afghanistan and left his family behind to seek a safer prospect. Tuesday, the uncertainty in his life became greater. He only knew one thing for sure. He could not turn around and go back home.

A father goes to war to finish son’s book

Courageous colleagues

New York Times reporter Stephen Farrell was rescued from Taliban clutches today, though his Afghan interpreter was killed in the raid to rescue them. Farrell had been captured last week in Kunduz, where he was reporting on a NATO airstrike that killed civilians.

The story generated conversation in the CNN newsroom about why reporters willingly place themselves in harm’s way; why they volunteer to go to war zones, natural disasters, police states and other hostile environments. I was asked the very same question at a foreign policy forum I attended a few weeks ago.

Certainly, no one has a death wish.

But I suppose the truth of the matter is that the adrenaline rush can be addictive. There’s something very powerful about feeling your heart race, knowing that you got the story even as danger lurks close by.

Still, journalists don’t travel to places like Iraq or Afghanistan to get shot at or roll over deep buried bombs. We go there because we care. We go there because we know the story won’t get out if we all decided to stay at home.

Today, I salute my brave colleagues who have put their own lives aside to bring the stories of others to life. I am relieved to know Farrell is safe; distressed that Sultan Munadi died in a hail of bullets that were fired in the raid. And extremely grateful for their courage.

Labor Day

Today is the last of the summer holidays. We celebrate Memorial Day, Independence Day and Labor Day with barbecues and pool parties. Or go off to the beach. Hang out with friends on our front porches.

On Memorial Day, we pause to remember all those who gave their lives in service of nation. On July 4, we mark the birth of the country. But on Labor Day, we tend to forget what the day is really about. So as you take a bite of your hamburger and drink a cold brew, think about all the people who fought hard to give working people the rights and protections we enjoy in America. Decent wages, time off, benefits.

In some countries, these are not a given.

This Labor Day is somber for me. So many of my journalist friends are out of work and struggling to find jobs. They are smart, talented and creative people who are willing to work hard for a living.

I am thinking of them, especially on Labor Day.

Making Mimi proud

Every reporter will tell you that good editors are difficult to come by. Out of those handful, a rare breed is one who is not only a strong wordsmith and advocate but one who shows the kind of sensitivity needed to produce powerful human dramas. Non-fiction that reads like pure poetry.

I had the privilege of working with one such editor and decided I would nominate her for the Mimi, an award named after Mimi Burkhardt, an editor at the Providence Journal who died unexpectedly a few years ago.

Her obit said this:

“Reporters loved to have Mimi as their editor because they knew she would always make their stories better,” said Carol J. Young, deputy executive editor and longtime friend. ‘When she worked with reporters, especially on projects, she became as involved in the topic as they were. She kept in constant touch as they reported, she felt their angst as they wrote, and, when the project was over, she shared their pleasures of seeing it in print.’ One such project produced a story in 2003 when writer Kate Bramson reported the traumatic ordeals of a teenage girl raped by a classmate in Burrillville. The resulting story, “Rape in a Small Town,” won a $10,000 award from the Dart Foundation.”

Bramson helped set up an award named after Mimi. It is given every year to an editor who navigates through stories of trauma with the utmost caring. It is designed for an editor who thinks outside the box and supports his or her reporter all the way through the process, unafraid to stand behind unconventional tactics and to stand up for the work of his or her staff.

This year, Jan Winburn, my editor at the AJC, won the Mimi. We just returned from the award ceremony in Indianapolis (that’s Jan and me at the Mimi dinner). I am thrilled.

Here, then, is the nominating letter, which my former colleague Michelle Hiskey and two of Jan’s reporters at the Baltimore Sun, Lisa Pollack and Mike Ollove helped write. It will provide a better understanding of what a strong editor ought to be. And it will make us yearn for the days that newspapers regularly embarked on such projects.

Dear Judges:

We nominate Jan Winburn for the 2009 Mimi Award.

The reasons why she deserves this recognition are deep and varied. In all our collective years as working journalists, none of us can recall having worked with another editor with a better understanding of how to navigate the emotional landscape of assignments involving tragedy and trauma.

We honestly believe that no better editor exists.

Jan’s exceptional body of work is testament to the rare dedication and unique skill that she brings to stories of struggle, suffering, recovery and resilience.

What is most amazing is that often, these stories are inspired by ordinary news. You know the kind – the six-inch story buried on page eight of the local section that informs readers of an unexpected death of a child or a fatal accident. Jan has the uncanny ability to read such a story and recognize the value in delving deeper.

Other editors might reflexively reject an idea because of preconceptions. But Jan always perceives possibilities for unexpected opportunities for understanding the human heart.

Last year, I traveled to Iraq for a seventh time to write about a young Army chaplain who was responsible for the welfare of a thousand infantrymen. Jan immediately recognized the potential power of this story when other editors failed to see its merits.

Why spend so much time and effort to tell a story we can get from the wires? The editors questioned whether there was any new ground to be uncovered. They wondered if readers were suffering “Iraq fatigue.”

But Jan immediately saw the power in the chaplain’s tale. Here, in the heart of the Bible belt, the young Army officer provided the paper with a chance to explore the intersection of God and guns on the battlefield.

My reporting told Jan that the chaplain was under tremendous pressure. He had to stay steely strong to administer to soldiers who were both physically and emotionally scarred by war. He

had to deal with everything from death and grisly injuries to homefront issues of failing marriages and domestic violence.

I returned from a frightening trip to Iraq only to find Jan had broken her right arm. Jan invited me to come to her house, where we sat at the breakfast bar with notebooks and ideas until we were able to form the backbone of what she imagined as an eight-part series.

Once a draft had been written, Jan went into battle herself, as she always does for her reporters. She knew that in this day and age of newspaper journalism, an eight-part serial narrative would be a hard-sell.

She told the editors at work: Don’t say ‘no’ without reading what we have. Defeat me on content, not on newspaper philosophy.

Jan worked tirelessly for weeks to ensure that my efforts would not go to waste. She believed in the story and was not willing to compromise on content.

That’s the reputation Jan has built.

Many years ago, she worked with Baltimore Sun reporter Mike Ollove on a story he proposed about a couple, Mitch and Cookie Grace, of Altoona, Pa. Their only child, an athletic, college-educated daughter, was accused with her husband of a senseless, grisly double murder in Ocean City, Md.

Other editors instinctively included the Graces in the understandable revulsion of the crime. Why, they wondered, should we devote any attention to those associated with the alleged killer. But Jan realized that these parents loved their daughter as much as any parents and had devoted themselves to her upbringing in every way. The tragedy of their story was that all that love and commitment on their part did not keep their child from a final series of disastrous choices.

Many readers surprised themselves by sympathizing with Mitch and Cookie.

Once again, the story upended preconceptions and normal expectations. Such stories do not happen without an editor brave enough to journey down difficult roads. Jan has shown that she has the courage, curiosity and strength to do so, again and again.

The rewards for those attributes have been scores of stories that readers consistently find provocative and ultimately enriching.

We learned from Jan about the indelible link between reporting and writing: that successful narratives are not just the stuff of pretty writing (as some editors believe). Instead the power lies in intensive yet delicate reporting that yields intimate anecdotes and details that allow Jan’s reporters to write with authority from another person’s view.

Jan taught us how to approach a potential story subject in the most sensitive and honest way possible; how to get a reluctant source to feel comfortable sharing his or her story; how to pull readers into stories that they don’t even think they care about.

Jan’s talents come across clearly in “The Umpire’s Sons,” a story written by Baltimore Sun reporter Lisa Pollak, which won the 1997 Pulitzer Prize for feature writing.

The previous fall, a ballplayer for the Baltimore Orioles made national headlines for spitting on an umpire as they argued over a call. The ballplayer, commenting on the incident later, opined that the umpire’s skills had diminished after losing his son to a degenerative, often-fatal nerve disease. Almost parenthetically, many of the news stories added one other detail: the ump’s second son was suffering from the same disease.

When Lisa flew out to Ohio to interview the ump and his wife, the expectation was that she would interview them for a few hours, then fly home and write up a short piece. But Jan confirmed what Lisa suspected after her first conversation with the umpire: With more interviews and research, she might be able to tell a narrative that helped readers better understand what it was like for this family to lose one child and then desperately try to save another.

Jan not only had a vision for the story, but she was a

crucial resource as Lisa worked, helping her figure out what material was needed to bring the story to life, how to focus hours of material and how to structure the story to keep readers engaged. When other editors wondered, ‘what was taking so long,’ Jan ran interference, convincing the powers-that-be that time wasn’t going to waste, that they needed to get everything right and make the story as clear and concise as possible.

Jan is known for going the extra mile for her reporters. In fact, editors at her last job at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution chided her for not being “managerial” enough. For always putting her reporters and their work first.

Sometimes, that has meant that Jan has gone beyond her role as editor. She is a dear friend to us all. My own mother died in 2001 and Jan has stepped into the role of a surrogate mom at times when I have needed advice or reassurance. Or simply, a big hug. She called me every day when I was in Iraq if for no other reason than to let me hear a friendly voice in the middle of war.

She has been that kind of essential companion as well for my friend and colleague Michelle Hiskey,

In 2007, Michelle wanted to write a difficult first-person essay about her relationship with her father. He’s a professional golfer, and taught Michelle well enough to earn a college scholarship. The initial story was to be about parents teaching their skills to their children.

Jan took over the story, and knew — because of her friendship with Michelle — that Michelle’s relationship with her father was complicated. Jan always pushes her reporters to open the door we often don’t want to open.

Michelle gulped and said yes. In the midst of great change and stress in our industry, she wanted to grow and improve as a writer but she didn’t think this story was in her. She felt naked. Exposed.

All summer and into fall, she worked on it, then put it down. It seemed too hard, too risky. When she turned in a draft that had the most difficult episodes glossed over, Jan gave it back and said, “Go deeper. I know there’s more there.”

She gave Michelle the security she needed to press on by promising that the story would not run without her father’s prior reading. Michelle knew she could trust Jan. This is not a typical promise made to a source, but this wasn’t the typical story. It had the potential to split her own family, and Jan navigated this delicately. In retrospect, Michelle understands that Jan believed the story could help heal her family.

The unrequited search for Michelle’s father’s approval motivated readers to send their stories of never measuring up. Michelle thought she was alone in her story. But she wasn’t. Jan is able to pull out universal desires and fears in the stories she helps tell. We all have a rock in our lives we don’t want to turn over. Jan helps us do just that and see what’s underneath.

Jan Winburn is a friend, a mother, a tireless advocate. Most of all, she is an editor who pushes relentlessly for the integrity of stories and invests time in shaping the talents of journalists. If the purpose of the Mimi Award is to recognize a journalist committed to telling human-scale stories with the utmost empathy and verisimilitude, you would be hard-pressed to find a more able practitioner.

We heartily nominate Jan with the hope that you will give her the recognition she so richly deserves.

A great man

In the wee hours of the night, when all was quiet outside, the newsroom was sheer madness.

Teddy was gone.

Sen. Edward Kennedy died late Tuesday after battling brain cancer for many months. Friend and foe remembered him as the greatest senator of his time, a liberal lion whose roar will be sorely missed.

When I was not even six yet, my father bought a painting of JFK and RFK. It was 1968 and Bobby had just been shot dead just like Jack had been years before. My father carried that painting back to India. A pastel set in a rich royal blue background. Every time we left India, it found residence at my uncle’s flat until it became a permanent fixture there.

Perhaps that painting should have included Teddy as well. The three Kennedy brothers who, as my friend Joyce pointed out tonight, Indians love to love. They were America’s political dynasty much as the Nehru-Gandhi clan was in India. And they were kind to brown people.

Whenever I am home in Kolkata, I stare at that painting that still hangs in the guest bedroom of my uncle’s Park Circus flat. I look at it and think not so much about how great a political family the Kennedys are, but of family. Period. I try to imagine the day my father bought that cheap painting. I was not there, but I wonder what propelled him that day in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He made sure to always hang it next to a posterized black and white framed photograph of Mahatma Gandhi. I suppose my father admired those men. He would have said each was great in his own way.

As for me, well, I have surrounded myself with photographs of my own father. There are days when I wish he were still here, among the living. Just so we could carry on one of our myriad conversations. Because in my little world, my father was the greatest man I knew. Or ever will.